Asynchronous code is important to understand in Node. It's used everywhere, and it's a part of a lot of the buzzwords you hear about why Node is so awesome, namely nonblocking I/O. I won't be talking about how it's implemented in this part of the tutorial since I find that for getting started with this concept, programming with asynchronous code lets the concept speak for itself. That being said, this concept is everywhere in Node, so once you have a good sense of how it's used, there are a lot of tutorials on how asynchronous JavaScript works, so at the end of this tutorial I will be linking to some tutorials that I recommend reading for a more in-depth understanding of how asynchronous code works.

For this tutorial, we're mostly going to take a break from HTTP servers and try out this code from the command line. But not to worry, as the title implies, there will be sloths in this tutorial, as well as some great artwork from Sally Lee!

Also, one other thing before we start, as you will see in this tutorial, callback functions are everywhere in Node. If you don't understand callbacks or you need to brush up on how to use them, I recommend this tutorial on callbacks at JavaScript is Sexy.

Anyway, as you've probably heard, Node.js is known for being fast, but surprisingly, Node is single-threaded, which basically means it can only do one thing at a time. This doesn't seem like much of a selling point, but because of the use of asynchronous code for slow stuff like file I/O and interacting with databases makes it so that as the slower code is being run, the one thread can keep going, making that one thread really fast. This is important because if the thread gets held up, and that thread is being used to serve your web app, everyone has to wait for the thread to finish the processes keeping it from continuing, so we want to make sure the slower processes don't hold up the thread so we can keep that kind of waiting in the era of scratchy dial-up tones (even though that sound was kinda awesome).

But enough of me talking about what this asynchronous code is used for without seeing it in action. Let's try out some asynchronous JavaScript!

Let's say we have a mother sloth who is going grocery shopping. She has four grocery lists, each with things in one aisle, and she wants them to be in order since it takes forever for a sloth to climb through a whole grocery store, let alone the checkout line.

To get the grocery lists, make a folder called sloths and copy this to a file

in sloths called grocerylists.js and run it with node grocerylists.js:

var fs = require('fs');

fs.writeFileSync('aisle1.txt', 'Hibiscus juice\nHibiscus flowers\n');

fs.writeFileSync('aisle2.txt', 'Carrots\nLeaves\n');

var aisle3 = fs.openSync("aisle3.txt", 'w');

fs.writeSync(aisle3, 'Pillows\n');

for (var i = 0; i < 5000; i++)

fs.writeSync(aisle3, 'ZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZ\n');

fs.writeSync(aisle3, 'Blankets\n');

fs.writeFileSync('aisle4.txt', 'Algae shampoo\n');

Now the sloths folder will have the grocery lists generated. As I mentioned in my last tutorial, Node can be used for things other than web servers, like making scripts for automating tasks. And generating aisle3.txt by hand would be really annoying to do, so Node scripts really come in handy here.

So, we have the files. Now to get them in order.

Put this into first-attempt.js:

var fs = require('fs');

fs.readFile('aisle1.txt', function(err, data){ //1

if (err) //2

throw err;

console.log(data.toString()); //3

});

fs.readFile('aisle2.txt', function(err, data){

if (err)

throw err;

console.log(data.toString());

});

fs.readFile('aisle3.txt', function(err, data){

if (err)

throw err;

var lines = data.toString().split('\n'); //4

for (var i = 0; i < lines.length; i++)

if (lines[i][0] != 'Z')

console.log(lines[i]);

});

fs.readFile('aisle4.txt', function(err, data){

if (err)

throw err;

console.log(data.toString());

});

Here's what's going on:

1. The main function we are using, fs.readFile, takes in the name of the file we

want to read and a callback function that gets called after the file is read.

2. The callback's first parameter, err, represents any errors that occurred

during the call to fs.readFile (which is null if there are no errors). We handle

errors in these calls to fs.readFile by throwing them.

3. The callback's second parameter, data, represents the contents of the file.

In the callbacks for each call to fs.readFile, we log the items for the grocery

list with console.log.

Also, note the use of data.toString(). In fs.readFile, the data starts out as

a Buffer, so if we simply did console.log(data), we would just get back the

hexadecimal representation of the text rather than the text itself, so we convert

it with Buffer.toString().

4. When the mother sloth was writing aisle3.txt, she was writing down pillows and blankets, but then she needed to get her 16 hours of sleep* so she fell asleep with her claw on the Z key, leaving 5000 lines of Z's between pillows and blankets. So to process the data in aisle3.txt, we are splitting the data into lines and only logging lines that don't start with Z.

Now run node first-attempt.js and you should get something like this

or maybe this

Pretty much it could be anything, but it's rarely ever the right order. Those files are being read at the same time, and while the files for aisles 1, 2, and 4 are short, aisle3.txt is really long, so it's almost always the last one to be written even though reading started for aisle3.txt before aisle4.txt.

And since the files for aisles 1, 2, and 4 are so close to each other in length, what order the three calls to fs.readFile() finishes in is not guaranteed.

Well that's inconvenient. But what if there was a way to read them in the order we called them in? Well, actually, we can. Write this in grocery-sync.js:

var fs = require('fs');

var aisle1 = fs.readFileSync('aisle1.txt'),

aisle2 = fs.readFileSync('aisle2.txt'),

aisle3 = fs.readFileSync('aisle3.txt'),

aisle4 = fs.readFileSync('aisle4.txt');

console.log(aisle1.toString());

console.log(aisle2.toString());

var lines = aisle3.toString().split('\n');

for (var i = 0; i < lines.length; i++)

if (lines[i][0] != 'Z')

console.log(lines[i]);

console.log(aisle4.toString());

fs.readFileSync is the synchronous version of fs.readFile. Instead of the results of reading the file going into a parameter for a callback function, the results of fs.readFileSync are returned as a Buffer. The rest is basically what happened in the callbacks of each call to fs.readFile in the last file.

Now run it with node grocery-sync.js and you should be getting this:

We have the right order and much simpler code now but there's one problem. fs.readFileSync and the synchronous versions of many other asynchronous functions work by holding up everything else going on in Node's one thread, which is called blocking. So if the mother sloth wants to brew some hibiscus tea, she can't do that while the script is reading aisle3.txt.

But what if when we called fs.readFile for one file we had the callback of that read call fs.readFile for the next read? Then we'd still be using the asynchronous version of fs.readFile, so the thread wouldn't block and as the files get processed, the mother sloth could drink some hibiscus tea.

Put this code into grocery-callbacks.js:

var fs = require('fs');

fs.readFile('aisle1.txt', function(err, data){ //1

if (err)

throw err;

console.log(data.toString());

fs.readFile('aisle2.txt', function(err, data){ //2

if (err)

throw err;

console.log(data.toString());

fs.readFile('aisle3.txt', function(err, data){ //3

if (err)

throw err;

var lines = data.toString().split('\n');

for (var i = 0; i < lines.length; i++)

if (lines[i][0] != 'Z')

console.log(lines[i]);

fs.readFile('aisle4.txt', function(err, data){ //4

if (err)

throw err;

console.log(data.toString());

});

});

});

});

for (var temp = 30; temp <= 212; temp++) //5

if (temp == 212)

console.log("Tea's ready!");

Run node grocery-callbacks.js and you should get this:

So here's what's going on:

1. The first call to fs.readFile gets the contents of aisle1.txt, checks for an error, logs the file's contents, and then calls the second call to fs.readFile.

2. The second call to fs.readFile gets the contents of aisle2.txt, checks for an error, logs the file's contents, and then calls the third call to fs.readFile.

3. The third call to fs.readFile gets the contents of aisle3.txt, checks for an error, processes the file's contents, logs the grocery list items, and then calls the last call to fs.readFile.

4. The last call to fs.readFile gets the contents of aisle4.txt, checks for an error, and logs the file's contents.

5. While this is going on, the mother sloth is brewing her tea and is drinking it as the asynchronous code prepares her grocery list.

Now the code works and the grocery lists are in order. And notice how as all the files were being processed, some tasty hibiscus tea was brewing and was ready before the first file was even read? This is what people are talking about when they mention how awesome Node's nonblocking I/O is. As I mentioned earlier, when those calls to fs.readFileSync were going on, Node was blocking, so anything after those calls would happen after they finished, and code for I/O is some of the slowest code out there. This is why we want to use the asynchronous versions that are nonblocking so other things going on in the program don't have to wait. So next time you have some hibiscus tea, remember that its fruity-minty flavor is brought to you by nonblocking I/O!

So, it looks like we tamed the beast of asynchronous code. Well, we did get the code to work in the correct order, but as far as style goes, there's still a problem.

See how we have all those nested callbacks? Those end up making the code go further and further to the right with each callback, creating what we Node developers call "The Pyramid of Doom", or "Callback Hell".

Callback Hell is a common problem in Node, but with many solutions, and to hear about ways out of Callback Hell, I highly recommend giving callbackhell.com a read. I will present one of the solutions, which is giving the callback functions names instead of defining them on the fly. Put this into named-callbacks.js:

var fs = require('fs');

var aisle1 = function(err, data){

if (err)

throw err;

console.log(data.toString());

fs.readFile('aisle2.txt', aisle2);

};

var aisle2 = function(err, data){

if (err)

throw err;

console.log(data.toString());

fs.readFile('aisle3.txt', aisle3);

};

var aisle3 = function(err, data){

if (err)

throw err;

var lines = data.toString().split('\n');

for (var i = 0; i < lines.length; i++)

if (lines[i][0] != 'Z')

console.log(lines[i]);

fs.readFile('aisle4.txt', aisle4);

};

var aisle4 = function(err, data){

if (err)

throw err;

console.log(data.toString());

};

fs.readFile('aisle1.txt', aisle1);

for (var temp = 30; temp <= 212; temp++)

if (temp == 212)

console.log("Tea's ready!");

The callback functions are a bit redundant, but now the callbacks still run in

order with no Pyramid of Doom.

Here's how it works:

- fs.readFile('aisle1.txt', aisle1) reads aisle1.txt and then calls the aisle1 function as its callback to process the contents of the file.

- aisle1 displays the contents of aisle1.txt and then calls fs.readFile to read aisle2.txt with aisle2 as its callback function.

- aisle2 displays the contents of aisle2.txt and then calls fs.readFile to readaisle3.txt with aisle3 as its callback function.

- aisle3 processes the contents of aisle3.txt and then displays the grocery list items and then calls fs.readFile to read aisle4.txt with aisle4 as its callback function.

- aisle4 displays the contents of aisle4.txt, finishing off the series of callbacks.

Like before, the mother sloth can make some hibiscus tea while this is all going

on.

Now, while the mother sloth was grocery shopping, her baby sloth was at Sloth

Preschool, where sloths learn important skills of slothfulness, like how to

climb trees, take a nap in the branches, and find leaves to eat. And today is

an important day in Sloth Preschool. Today the baby sloths will be singing the

Sloth Alphabet, which of course is:

(save this to alphabet.txt)

ZZZZZZZ, ZZZZZZZ, ZZZZZZZ, ZZZ, and another Z

Now I know my ZZZ's! In 9 hours I'll climb some trees.

And the mother sloth wants to take a picture with her baby and post it on her website. But the family photo has to be after her baby is finished singing, so how do we do that?

First save this to alphabet.html:

<html>

<head>

<title>Sloth family photo</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>My baby sloth knows the alphabet!</h1>

<img src="http://localhost:34313/sloths.jpg" />

</body>

</html>

Then download this and save it to sloths.jpg in the sloths folder:

Then save this to alphabet.js:

var http = require('http'),

fs = require('fs');

var SLOTH = 'image/jpeg';

http.createServer(function(req, res){

if (req.url == '/sloths.jpg') {

fs.readFile('sloths.jpg', function(err, data){ //1

if (err)

throw err;

res.writeHead(200, {

'Content-Length' : data.length,

'Content-Type' : SLOTH

});

res.end(data);

});

}

else {

fs.readFile('alphabet.txt', function(err, data){ //2

if (err)

throw err;

fs.readFile('alphabet.html', function(err, data){ //3

if (err)

throw err;

res.writeHead(200, {

'Content-Length' : data.length,

'Content-Type' : 'text/html'

});

res.end(data, 'UTF-8');

console.log('Finished sending the HTTP response'); //4

});

console.log(data.toString()); //4

});

}

}).listen(34313, function(){console.log('Now listening on Port 34313!');});

and run it with node alphabet.js

and if you request localhost:34313, you should get this:

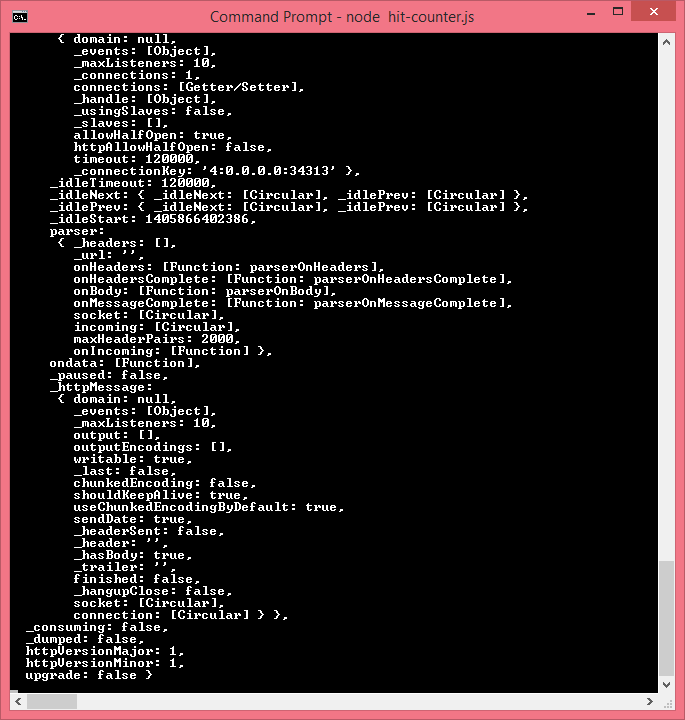

with this in the console

Here's how it works:

1. When sloths.jpg is requested the filesystem reads in the picture asynchronously, checks for an error, and then sends the picture in JPEG form (with the "SLOTH" Content-Type) as the response, just like in the example in the last tutorial.

2. When the main page is requested, the filesystem first reads in alphabet.txt

3. In its callback, it checks for an error and then calls fs.readFile for the

HTML page at alphabet.html, which is sent as HTML in the callback to that call to fs.readFile

4. At the end of the callback for reading in the alphabet, the sloth alphabet is printed to the console. At the end of the callback for reading in the HTML, "Finished sending the HTTP response" is printed to the console. Notice that the sloth alphabet is printed first. This shows the asynchronous code in action again; while the filesystem is reading the HTML page, Node can output the contents of alphabet.txt.

So now we've seen asynchronous code, how it avoids blocking the thread, how synchronous I/O can be used to do I/O in order, how to impose an order on your asynchronous code when you need things to be in order, a way to avoid Callback Hell, and how asynchronous code can be used on an HTTP server in Node.

This should give you a good starting point for understanding asynchronous code in Node, but as I mentioned before, this tutorial was meant to only scratch the surface. To get a stronger understanding and hear about how this works internally, I recommend taking a look at these tutorials for the JavaScript event loop in general:

http://ejohn.org/blog/how-javascript-timers-work/

http://blog.carbonfive.com/2013/10/27/the-javascript-event-loop-explained/

And this screencast to hear more about asynchronous JavaScript works in Node.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l9orbM1MJNk

For this tutorial, I'd like to thank Sally Lee for drawing these adorable pictures of the sloths and the Sloth Sanctuary in Costa Rica for showing the world how cute sloths are! Next up, time to move on to express.js!

*NOTE: Sloths don't actually sleep 16 hours a day. They actually sleep more like 9

hours a day, so about as much as a college freshman.